June 28 marks the 25-year anniversary of one of Southern California’s largely forgotten natural disasters – the Magnitude 7.3 Landers earthquake, which marked the zenith of a sequence of quakes to rattle the High Desert in the 1990s. Besides causing significant damage and stoking fears of an apocalyptic megaquake that thus far has not occurred, the Landers earthquake sequence was a pivotal event in the development of seismological science.

While Southern Californians were preoccupied with the aftermath of the riots that followed the Rodney King verdict in spring 1992, a remarkable seismic episode was developing in the High Desert about 140 miles east of Los Angeles.

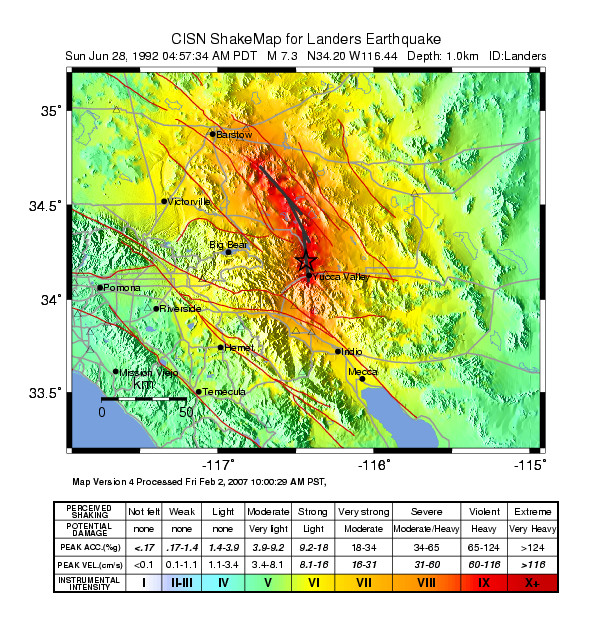

On April 23, 1992, a Magnitude 6.1 quake struck the Joshua Tree area, followed by numerous aftershocks. Two months later, the strongest quake to hit the state in 40 years (Magnitude 7.3) rumbled through Landers at 4:57 a.m. on the last Sunday morning in June.

Thankfully, the area worst affected was relatively sparsely populated, though damage was still substantial. At least two people died, more than 400 were injured and damage was in the hundreds of millions of dollars, primarily in the Yucca Valley and 29 Palms communities. The shaking was felt in such distant locations as Boise, Denver and Phoenix.

Who Was at Fault?

While most earthquakes are believed to occur on a single fault zone, the Landers event was unique in that it ruptured several faults. At least five distinct fault zones were involved: Johnson Valley, Landers, Homestead Valley, Emerson and Camp Rock.

A 53-mile surface rupture – the scientific term for a crack in the earth caused by a quake – opened up, extending from Yucca Valley to south of Barstow. Due to the arid climate of this area and lack of major human development, the scars were visible for years.

The Big Bear Quake

June 28, 1992 was a horrific day for many local residents. Aftershocks occurred almost continuously, though only the largest were felt in the Los Angeles metro hours to the west.

The worst aftershock occurred at 8:05 a.m. that morning. It was a Magnitude 6.2 quake in the Big Bear area, which caused significant damage in the mountain resort town, some 20 miles west of the initial temblor. Because it was closer to the Southern California metropolis, it was felt strongly by more people.

ABC World News Tonight on the Landers Quake, June 28, 1992

Landers and the Big One

With so much seismic activity, California officials feared that a devastating quake could soon shake the Los Angeles area. An unprecedented warning was issued, urging residents to avoid freeways and tall buildings. As seismic activity declined later that day, however, officials decided to rescind the order, and millions of Southern Californians commuted to their jobs the following Monday morning.

Still, nerves were raw for years afterwards. More than 40,000 aftershocks, most too small to be felt, would rattle the High Desert. On Oct. 16, 1999, a Magnitude 7.1 quake struck Hector Mine, a remote part of the desert northeast of Landers, causing another spectacular surface rupture, though no significant damage.

The extreme levels of seismicity may have inhibited the urban development of the Yucca Valley area during the boom years of the 1990s and 2000s.

The Landers quake provided an opportunity for extensive and unprecedented seismic research. Within months, two competing theories developed. On the one hand, some experts feared that the quakes might push the nearby San Andreas Fault to the breaking point, leading to a catastrophic event in the Magnitude 7.5-8.0 range in the Los Angeles and Inland Empire metros. On the other, some theorized that the massive energy released by the Landers quake may have relieved stress on the San Andreas.

A few seismologists and quite a few amateur earthquake watchers have theorized that the Landers quake represents a shift in the San Andreas Fault itself (i.e., that the much-feared fault has moved to the east). This would be good news, as it would shift the greatest threat away from the Southland metros, though much more data is necessary before such a hypothesis could even be codified into a coherent theory.

For More Information

For more on the Landers earthquake sequence, check out the fall 1992 edition of Arizona Geological Survey, or the November 1993 report, “The 1992 Landers Earthquake Sequence: Seismological Observations,” published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.